Hurried child syndrome is impacting too many children and teens. What is it and how can we avoid it? 10 tips for parents and teachers.

My friend James and his wife had a baby girl on Friday; her name is Matilda. At work on Monday, I asked him if Matilda could read yet. James replied, “She hasn’t had time, we’re working on her algebra.”

It was silly banter between two pretty nerdy teachers. However, it reflects our experience of a society that rushes children to grow up too quickly; socially, emotionally and academically. The problem is widespread and at its most extreme can present as a stress disorder called ‘hurried child syndrome’.

What is hurried child syndrome?

Dr David Elkind, is the child psychologist and author who coined the term ‘hurried child syndrome’. He describes it as “a set of stress-linked behaviours, which result when a child is expected by his (her) parents to perform well beyond his or her level of mental, social or emotional capabilities. Basically, parents overschedule their children’s lives, push them hard for academic success, and expect them to behave and react as miniature adults.”

We can look at that description and say, “Well that’s obviously bad”, and it’s true, most people are not that extreme. However, rushing children sneaks up on us. In day-to-day life, what does that look like?

Well, it looks like this:

- Taking children to tutors so they can read before they start school

- Sharing with children marital or financial problems

- Bombarding kids with the idea that success is all-important and winning is everything

- Subtle messages about the importance of grades and the idea that choices at school will determine their WHOLE lives

- Expecting kids to always be disciplined, organised, socially aware and never grumpy or argumentative

We need to examine the messages we are sending our kids and more importantly, the lifestyle we are modelling. Perhaps COVID-19 has been an opportunity to slow down and reflect, have we been making rushing and winning the norm?

Why do we hurry children?

Being part of western society means constantly marinating in a culture that values achievement and success. We have internalised the idea that ‘winners are grinners’ and unfortunately, we pass this on to our children. Our society sees awards and recognition as so important that they sometimes eclipse our deeply inherent knowledge that children need to be children.

Most parents have the very best of intentions. It seems natural to want more for their children than they had themselves. Consequently, some see hurrying their kids as a gift. They may also fall into the trap of constantly pushing for success as a protection against the pain of failure. Unfortunately, they are working against nature; growing up and developing skills takes time, and failure is invaluable to learning, children need it.

Consumerism adds to these problems. The people designing marketing campaigns are very aware of the ‘pester power’ of children and the impact that has on parent spending, so they market directly to children. Often marketers are selling children ideas of success well before it is appropriate. The fact that so many children have smartphones from a young age allows marketers easy access. Smartphones pull children into an adult world.

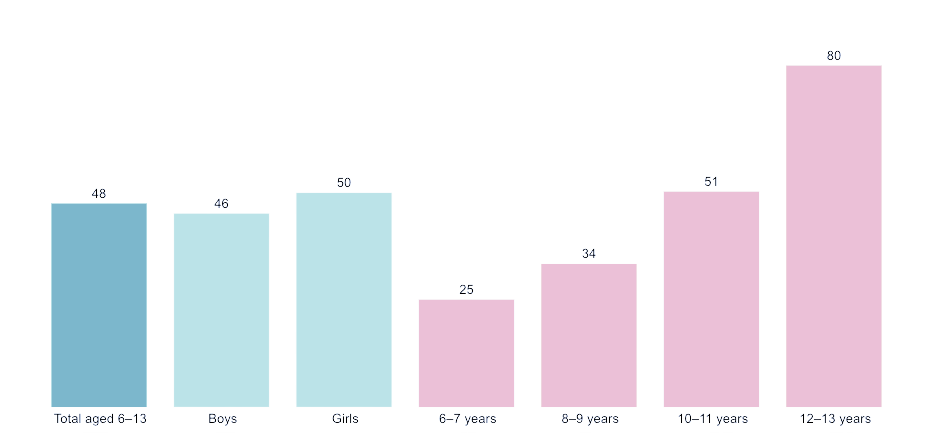

Source: acm.gov.au

Hurrying through learning

School is an environment where comparing one child to another is almost inevitable as they are so conveniently separated into age groups. It is easy to see how it could become a thirteen-year race to graduation. Government testing and exams don’t help as they teach children to focus on grades and comparisons instead of learning itself.

When teachers hand back assessments there is a buzz around the room as students compare marks. When they get home, they are quick to say whether or not they ‘got above the average’. It doesn’t really matter what that average mark is or what knowledge it represents; it’s abstract.

Ms Cathy Hains is Deputy Principal of Middle School at Lourdes Hill College. She says, “When students focus only on the exams, they miss the richness in the learning around them. They miss the opportunities to spark interests that could become passions.”

They also miss the opportunity to gather the skills they will need in the future. Ms Hains says, “Students need time to learn to problem-solve and be creative. They need to connect their learning to life and that takes time. In any career or life, there will be challenges. Kids need a toolbox of strategies and skills and they need lots of opportunities to practise using them.”

The impact of hurrying children

When we continually hurry children and expose them to expectations and experiences that are not age-appropriate, we create long-term stress. Stress that lasts for more than a couple of days, such as that experienced by a hurried child, has negative effects. The constant flood of cortisol actually damages the brain and makes it harder to lay down memories. This kind of stress can have a devastating impact on mental health, physical health, and even brain development. It also makes for a pretty miserable childhood!

How can we ensure our children are not hurried?

1. Recognise your child needs a childhood. Protect it by reassessing the schedule.

2. Avoid falling into the trap of equating your child’s success with your own.

3. Limit technology, it exposes children to the adult world before it’s necessary.

4. Talk about the future positively and hopefully.

5. Help your children set goals that are personal and meaningful to them.

6. Talk about a whole myriad of possibilities for their life, not just ‘get a good mark and go to university’.

7. Introduce them to adults who have done life differently.

8. When they sit an assessment, ask them to tell you about all the things they learnt that weren’t on the test. Value that learning.

9. Always link learning to life, make it relevant, and bring it to life.

10. Don’t share adult problems with children, they are not your friend or confidante, and they need a parent.

In conclusion…

My friend’s little daughter Matilda is very lucky. She has the good fortune of being born into a loving family in a country that can offer her a safe and rich childhood. She has wonderful opportunities ahead of her, but all in good time. All in good time.

This article was first published on Inspiring Girls, a product of Lourdes Hill College, Brisbane.