I grew up on a farm. All that space gave my brothers and me ample opportunity to develop what my mother called, our ‘outside voices’. We lived life out loud. However, there was one time of the day when silence reigned supreme, 7 pm when the ABC News was on the television. Perhaps that designated silence gave news a revered place in our childhood.

Because news was perceived as important in my generation, I always felt a little frustrated as an English teacher when I tried to relate novels, poetry, or any text to what was going on in the world. My students simply didn’t have the historical or current affairs understandings needed to effectively make meaning. It’s a problem that seemed to be growing worse by the year. Until this year…this fiery, confusing, year of the virus.

This year the news has been relevant to all of us, COVID-19 has made certain of that. So, are our kids engaging with current affairs now?

Are young people engaging with news?

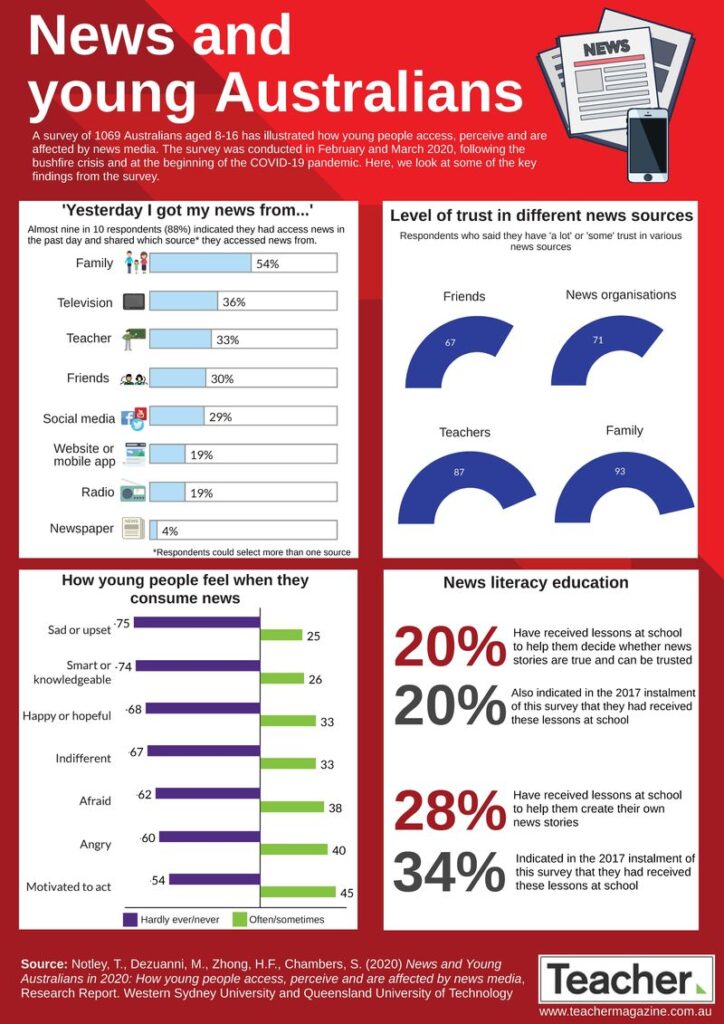

In February and March of 2020, 1069 young people aged between 8 and 16 participated in survey research by the Queensland University of Technology and Western Sydney University. Almost 9 out of 10 respondents said they had accessed news within the past 24 hours which sounds promising. They then shared where they accessed that news. They were able to select more than one source.

I expected the majority to select television and social media. I was completely off target. 54% got news from their family. Television came in at 36% and teachers accounted for 33%. As you can see from the infographic below, the vast majority of news was delivered by another person in their lives.

There are a couple of interesting ideas we can take from this result:

1. Most children are simply not reading news anywhere at all and very few are watching television news.

2. The news our children do receive is highly filtered. It comes via family, teachers and friends so the values of those people have a strong influence on how children receive that news.

The research also examined the level of trust that children and adolescents have in their news sources. They trust parents and teachers more than they trust news organisations. 90% said they had ‘a lot’ or ‘some’ trust in their parents as a source, but only 71% said the same of news organisations. Interestingly, they saw friends as the least reliable source.

Lived experience

David McKenna is a Humanities teacher at Santa Maria College. Over the course of his 30 years in education, he has shared a special interest in news with his students. He acknowledges that yes, students will engage with a subject like the pandemic, because it is an exceptional story and highly emotional, however, “Their understanding is superficial, and they are largely interested in the personalities at play. They will know about ‘ScoMo’ and McGowan, but most couldn’t tell you which parties they represent or how the National Cabinet relates to the Federal Government. They are also unable to see the way the media and politicians are manipulating news.”

What I found most interesting about my discussion with Mr McKenna was his belief that this lack of engagement with current affairs probably won’t influence our young people in the long term, in their daily, comfortable lives. “It is completely possible to get through high school without having any understanding of politics or ‘hard news’. Then, once a child gets to university or the workforce, they develop highly specialised knowledge for their career. And does it matter?”

The fact that it seems not to matter is the privilege of living in a country that is doing well and is relatively well-governed. It is only when leaders come to power who threaten our way of life and freedoms that it will be a problem. By that stage, will we have citizens who are engaged enough to protest? Or will they be lulled by personality as they have been in many parts of the world?

What next?

Now more than ever, we need to be teaching our children and teens critical literacy. When surveyed about critical literacy lessons, only 20% of students said they had been taught how to discern the legitimacy of news in the previous 12 months. Given that critical literacy is fundamental to the Australian Curriculum, I would argue that students may not be reporting accurately. It is likely they are being taught critical thinking skills but are not able to transfer those skills to different situations, including reading the news.

3 ways to help build kids’ news literacy:

1. Watch or read news with your child from a number of different and opposing media outlets.

2. Talk about what techniques used by news producers could create bias in content.

3. Talk about who owns the news and what their interests might be.

Obviously, the way you explore these ideas will be dependent on the age and maturity of your child. Narrative and visuals work best. Mr McKenna says, “The saving grace is that the documentary genre has evolved to be so powerful. Recent documentaries are so engaging and produced with all the light, colour and quick editing that kids enjoy. They are one of the best ways of teaching complex issues today.”

Finally…

It is highly unlikely that we will ever return to a time when the news bulletin is revered and maybe that’s okay. However, we do need to find a way to ensure our young citizens are informed and have a working knowledge of the way our country is governed. Otherwise, our lack of awareness may lead to the biggest news story of all.

Linda would love to meet you on her Facebook page here