Is it possible to meet the needs of adolescents without completely destroying your own well-being? YES

Does any of this look familiar?

- You’re ringing the school to report that your child hasn’t done their assignment and is feeling anxious about it.

- You are feeling resentful at home because you are doing all the housework and chores that keep things ticking along, and your children are not contributing.

- You have limited time because you are continually driving your kids around and accommodating their social plans.

- Your child is in high school but it’s up to you to find lost items, pack lunches, and cook all the meals.

- Routinely, your child loses their cool, and then so do you.

The popular response in social media is ‘more wine’ and memes that say ‘You know you’re a parent when…’ This situation is being normalised. Some parents even wear it as a badge of honour. I’ve had parents say things like, “I do everything for my kids, it’s how they know I love them.”

Alarm bells. That’s not a love language, that’s a problem.

Too often, both at home and at school, we are rescuing our kids and teaching them helplessness. We aren’t empowering them to show us how incredibly capable they can be.

Use a wider lens when looking at the needs of teenagers

Don’t get me wrong, I am not advocating a return to the ‘good old days’, which frankly weren’t all that good. We don’t need more tough love and we don’t need more punishment. What we need is a wider lens.

When we pull back and look at the big picture, we can ask what is it we are trying to achieve in the long run? What do we want for our kids’ future and who do we need to be to make that happen?

Kristina Morgan is a clinical psychologist at Lourdes Hill College. In her work, her experience is that most parents will say they want their child to be happy. “They think happiness is something they can give their child. It’s not. Happiness is built from basic skills we need to teach.”

Our kids need in adolescence, to learn to:

- treat themselves and others well,

- problem solve effectively,

- manage the ups and downs of their lives in a calm, regulated way,

- have healthy, reciprocal relationships, and

- function well INDEPENDENTLY of us.

That last one is super important but probably the hardest to embrace.

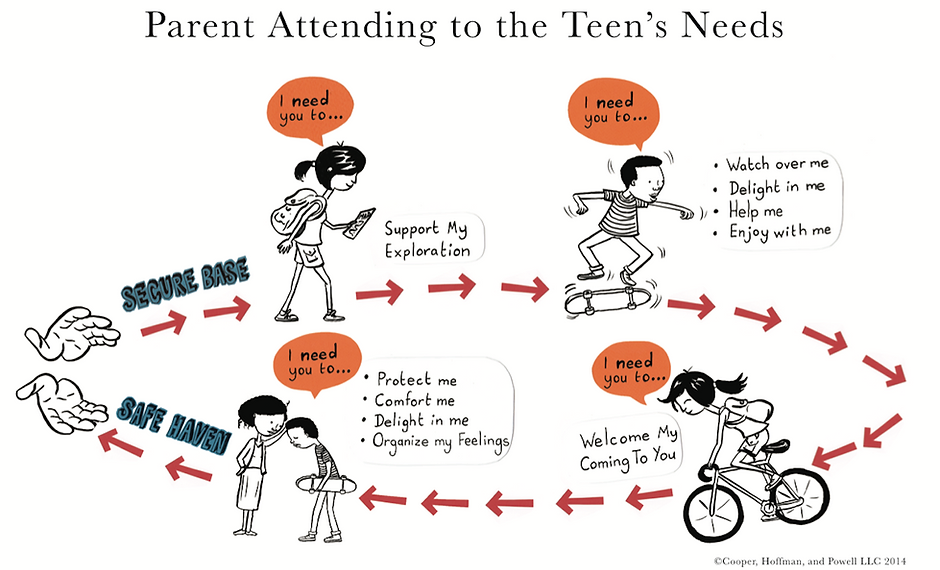

Circle of Security – The Needs of Adolescents

A well-respected theory that takes a wide-lens view of child and parent relationships is the Circle of Security. It clearly illustrates the circumstances required to help kids thrive.

It states that we need to provide three things:

1. A secure base from which a child can go out into the world. This secure relationship lets them feel comfortable going into new experiences and taking considered risks. They can enjoy and explore the world knowing they have the skills and support they need.

2. A safe haven a child can return to for reassurance, guidance, and love. Knowing that you are a haven they can return to when things are difficult allows a child the opportunity to share challenges. They don’t need you to fix things for them, they need you to listen, help them organise their feelings and depending on their age, help them to solve problems on their own.

3. A kind and regulated adult presence in the child’s life. The greatest indicator of a child’s resilience is the presence of a secure adult who listens and can regulate their own emotions. Our job is to always be calmer than our child.

In this approach, the focus is not on what we DO for our kids, it is on who we need to BE for them. Our job is to BE STRONG, WISE, and KIND for them.

What does the circle of security look like in practice?

That’s all very nice in theory and it makes sense, but what does it look like in everyday parenting and teaching? Kristina offers these indicators for us to consider.

1. Adolescents practise making decisions and adults don’t take over. They listen and discuss but the responsibility for the decision rests with the young person. These opportunities let them know we trust them, and they learn they are capable.

Obviously, decision-making needs to be age-appropriate, but in teens, it would include things like deciding how they might resolve their friendship issues; deciding how they will get to and from their part-time job; or deciding how they will plan their week, so all their schoolwork is done and they also have time for sport, jobs, and fun.

2. Adolescents think for themselves. They don’t passively wait to be told what to do all the time. This is greatly improved if you have established processes and routines in your home or classroom. When the basics are covered by habit, there is room for initiative.

3. Adolescents have responsibilities. Kristina says, “It is important that kids be given some responsibilities, not just for themselves but also for their family.” For example, at mealtimes, it is appropriate for everyone who eats to have some role in the process. They can help cook, set the table, stack the dishwasher, or package leftovers.

Other responsibilities may have a more relationship-centred focus, like walking down the road to Nan’s place each day to say hello and check on her; or walking a sibling to school. Kristina says these kinds of responsibilities teach kids that “In our family, we show up for one another.”

4. Adolescents experience natural consequences. If homework isn’t done, the natural consequence is they explain it to their teacher and maybe take a detention or some other sanction. That may be uncomfortable and inconvenient, but it promotes powerful learning.

When adults intervene and make problems go away, they prevent their children from learning. In this case, the lesson is, that we all have obligations in life that need to be met.

5. Adolescents understand which emotions are appropriate to a situation. In her daily work, Kristina finds that often children are protected from their emotions. When they do eventually experience them, they feel unnatural and overwhelming.

A good example is a student who hasn’t studied feeling incredibly anxious on the day of an exam. They need to understand that anxiety is an appropriate feeling for that situation. It is okay for your child to be uncomfortable. That discomfort will motivate them to study next time.

A parent insisting that the school excuse the child from the exam teaches them that situation-appropriate anxiety is a disaster or a mental health problem. It’s not.

What if you are already struggling with broken curfews, destructive decisions, and dishonesty?

As with all big problems, we need to go back to basics. Kristina says, “If you are fighting over big things, look at how you are following through on the small things.

“Do you let failing to unpack the dishwasher slide? Do you make excuses for them when they don’t get their work done? Is it okay if they don’t turn up for team sports because they don’t feel like it that day? Go back and make your teen accountable for the small things so they know who they are and who you are.

“Retrain your child to follow through. Make sure you follow through too, as your example is their most powerful teacher. Then build on the small wins by allowing more freedom for the big things.“

Final thought…

Parenting and working with teenagers will always be tiring to an extent. They are emotional and energetic and test the boundaries of who they are and who you are. So, yes, wine may help. However, that shift in focus from who we need to be for them rather than what we need to do for them will make all the difference.

This article was written by Linda Stade and first published by Lourdes Hill College, Brisbane, on their Inspiring Girls website.