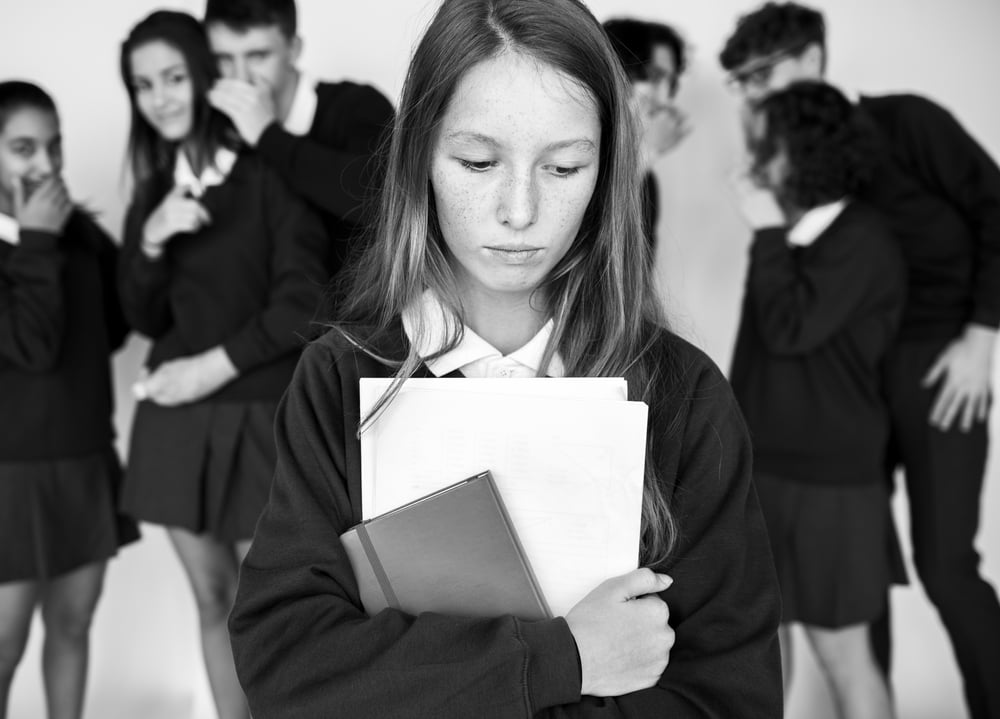

Being a teenager with no friends is an awful predicament in a social setting like school. How do we support them and create inclusion?

Yesterday, a twelve-year-old girl I care about, told me that at her school she has nobody to hang out with. In fact, in class when she sits next to other kids, they move away. She said at lunch and recess she just keeps moving from place to place so she looks as though she has somewhere to be and is busy. That way nobody will know she is completely alone.

This young girl is lovely and she used to have friends in primary school. However, when she got to high school her friends grew up quickly and she didn’t. She doesn’t share their interest in boys and fashion, and they find her little-girl ways embarrassing now, especially when at high school there are so many other people to choose from.

She’s very wobbly at the moment and there is no way to console her. I know she will be fine and one day she will be out in the world. This will be a bad memory. But she doesn’t know that yet, and the future is a long way away.

At some stage, most children will feel alone at school. It might be because they have just changed schools, it might be because they have had a falling out with friends, or maybe because they just don’t fit the mould. They’re different for some reason. When a child tells you they are alone at school, often they are telling you they feel vulnerable and that comes with fear and anxiety.

As a teacher, you create seating plans or have a quiet word with a few kids, so that nobody ever has to feel that way. But kids protest with their body language and their rolling eyes. Even the best kids get sick of doing the right thing all the time. It is hard to socially engineer inclusion. But we keep trying.

You can’t force kids to be friends and you don’t want to. Friendship is special. When adults tell children, “Everyone has to be friends”, we devalue the gift that a good friend is. We redefine friendship as an obligation. We also rob kids of the opportunity to learn how to choose and develop appropriate friendships.

You would think that there are enough of these kids who aren’t fitting in, for one reason or another, that they would band together. I have fantasies of them being united by their common circumstances and great awareness of pain. I see them taking on the world and supporting each other every inch of the way. But that’s not how it is.

Those kids who don’t fit in don’t band together, because they too believe that if you’re different then you’re not quite right. They don’t want to be associated with the ‘losers’ any more than anyone else. And so they stay alone. They hide in libraries and help teachers at lunchtime. The pure effort of not being noticed is exhausting.

Sometimes the kids who do fit in find sport in belittling those who don’t. It defines them as ‘in’ to point out someone who is ‘out’. My little friend had girls post a picture of her on social media. At the time they told her she looked pretty, but then they posted it with the words, “This face makes me cringe!” Following that were a number of other insults by other kids who also want to make sure that they are ‘in’. She was destroyed. And I have no words.

The hierarchy of kids’ social structure is brutal. We talk about queen bees and wannabees, but this is not a purely female phenomenon. Boys are just as likely to knock someone down in order to build themselves up. Traditionally it has been girls who were the master manipulators, and boys used brute force. However, with society’s increased disapproval of violence, boys have adapted. By all accounts, many have mastered the skills of belittling and exclusion.

So what can we do to help kids who don’t fit in?

As I said, we can’t socially engineer friendship, but there are things we can do.

1. We can reward respect. You don’t have to get on with everyone in life. You do have to show them respect. Everybody is different, and being different doesn’t make you wrong or a ‘loser’. There are lots of kids who recognise this and stand up for those under siege. Their bravery and integrity should be rewarded constantly.

2. Teach kindness. Kids should know that it doesn’t hurt to be kind. In fact, it feels quite good. They shouldn’t just know it, they should see it, by looking at the adult role models in their lives.

3. We can teach empathy. You know there is a gap in society’s skill set when Sesame Street starts trying to plug the hole. Recently they have been running a segment teaching empathy with the help of actor Mark Ruffalo.

Empathy is the ability to see from another person’s perspective and feel the way they would feel. If our kids were more empathetic, they would be more likely to make life easier for those who struggle.

4. Children need a firm understanding of what friendship is. It’s about shared values, interests and experience. It isn’t about power and fitting in. If kids could recognise real friendship, they would also be free to be kind and empathetic to people who aren’t their special friends. They would realise that those nice interactions don’t define their social status, just as their friendships don’t.

5. We need to encourage kids to be involved in activities outside of school. They need opportunities to be exposed to lots of different kinds of people. They will have more opportunity to meet new people and they would understand that maybe everyone isn’t the same as the kids at their school.

6. Encourage kids to be involved in co-curricular activities like service programs, art programs, drama, dance…anything that appeals to their special interests. That way they are in contact with people of different age groups who care about the same things as them.

I love sport for teaching kids about working together, recognising each other’s talents and having a shared goal. Sport also offers you skills that will always allow you to meet new people and quickly become part of a community.

And What About My Teenager With No Friends? What Can We Do For Her?

1. Listen carefully when kids tell you of their experiences. Let them know that you recognise their pain and that you are always open to listening. Try not to overreact, it won’t help and it sends the message that the situation is even worse than it is. Allow the child to sit with you and their feeling but don’t let them dwell, otherwise, it can be overwhelming. Get them into their safe routines and the happy rituals of your family. (Learn more here about how to respond to your child’s friendship issues)

2. Parents should try to work with the school without blaming them. Schools are no happier about this sort of behaviour than you are. They won’t be able to ‘fix’ it in an instant. This sort of situation is really delicate and requires well thought out strategies.

3. Encourage your child to try to make one friend at a time. Trying to fit into a group is hard and different dynamics are involved.

4. Sometimes you need to explicitly teach social skills. Santa Maria College has a program called Balance. It allows the kids the opportunity to spend time with the school psychologist, learn some emotional literacy and skills for making friends. As it is a group program they also meet other kids who for one reason or another might be struggling too. In a safe environment, they get to let their guard down and still their anxiety.

5. Offer her/him a safe place at recess and lunch. Libraries are a lifesaver. They offer kids safety and something to do. They also offer kids wonderful, amazing books. Books allow kids to travel into different worlds and lives. They tell kids, “You are not alone. Other people feel this way too”.

6. In a K – 12 school there is the opportunity to help with the very young children. This can be very affirming for an adolescent. Little kids love having older children working with them on the serious business of playing and learning. It gives a sense of worth and appreciation to a struggling child. There is a purpose.

Why not follow Linda’s blog? You’ll receive useful information to help support your kids as they navigate their school years.

Visit Linda’s Facebook page here

Linda Stade has worked in various teaching and management roles in education for twenty-five years. She has worked in government and private schools, country and city, single-sex and co-ed. Currently, she lives in Western Australia and works as a freelance writer and speaker.