Friendship issues can be devastating for our kids. Here are 6 tips that will help you respond powerfully instead of simply reacting.

You know that moment, when you pick your child up from school and something is deeply wrong? As they approach the car, the emotion is barely concealed behind a carefully managed mask. The facade will not cope with even a kind word. The emotion is just waiting to tumble forth.

More often than not, that sort of pain is brought about by friendship issues: mean words, exclusion, gossip, drama, and the sort of politics that happens in social groups. It happens in every school. Let’s face it, it also happens in workplaces and families and adult friendships. It doesn’t feel good and we don’t condone it, but it is very human.

Adults recognise this pain when we see it in children. Often it triggers in us memories of our own horrible experiences. Armed with our pain and theirs, we blunder forwards. In our efforts to make things better, we can exacerbate the problems; we react, instead of acting.

However, what if I told you, these tearful moments are a good thing? I know your hackles are rising, but stay with me. Lourdes Hill College clinical psychologist Kristina Morgan says, “Your child will fall, and they will feel overwhelmed. That’s okay. Believe it or not, you want that. They need the bumps to learn. You want them to find the gaps in their social and emotional competence so that you can support them while they fill those gaps.”

Positive social-emotional learning happens for your child when two vital elements come together:

- They have real emotional experiences.

- They see the way you positively respond to and manage those experiences.

This is the magic space where social-emotional learning happens for children… and parents.

Friendship issues – how to respond instead of reacting

Right from the very beginning of our children’s path through schooling we need to recognise that kids will not always get on. However, there are thoughtful ways you can approach your child’s experiences that will dramatically enhance their social and emotional learning:

1. Acknowledge differences in children and families

Children are different from one another; we love that, and we want that. The things that make them individuals are the gifts they will offer the world. Families are also different. They have different values and views of the world. These differences mean that sometimes there will be conflict. Recognise that and help children value difference.

2. Acknowledge the competency gaps

Schools are full of young, beginning learners. They are developing, trying and stumbling. It is inevitable that they make mistakes and fall into their competency gaps. Just as they learn to read and do algebra, children learn social skills, and they don’t always get them right.

To compound the problem, our children are working with brains that are still developing, so they are relying largely on instinct. The instinct part of the brain is fully developed by early adolescence, whereas the rational, judgement part of the brain doesn’t reach an adult state until the mid-twenties. Often what we see in young people experiencing friendship issues is a consequence of this discrepancy. Too much feeling and reacting, not enough reflecting and thinking.

3. Share your adult-state brain

When your child is experiencing conflict and pain, every instinct is to swoop in and solve the problems. Please don’t. When we rush in to save a child, they receive two very clear messages:

- This situation is much worse than I thought it was

- I’m not capable of fixing my own problems

What you can do, which will make a big difference in the future, is to share your adult-state brain. That means, bring the calm and coach your child, rather than taking over. You can support your child and let them know you’re there for them. You can stand by their side and ask, “What’s your plan? I believe in you and I’m going to support you. Together, we’ve got this.”

4. Sit with your discomfort

Not swooping in to fix things is easier said than done. It involves us dealing with our own negative feelings. Ms Morgan says, “When you react from your discomfort and race to fix things for your child, it makes YOU feel better. It doesn’t make anything better for your child; no learning takes place and no skills are practised.”

Please don’t confuse this ‘standing back’ with tough love. Ms Morgan emphasises,” I am not talking about tough love. Tough love doesn’t offer connection or support. Tough love walks away and leaves the child alone and groping around in the dark for skills they don’t even know are missing. Your calm allows your child to manage their own feelings. It lets them practise thinking for themselves.” We need to recognise that distinction between supporting and rescuing our children.

5. Recognise this is a skills problem

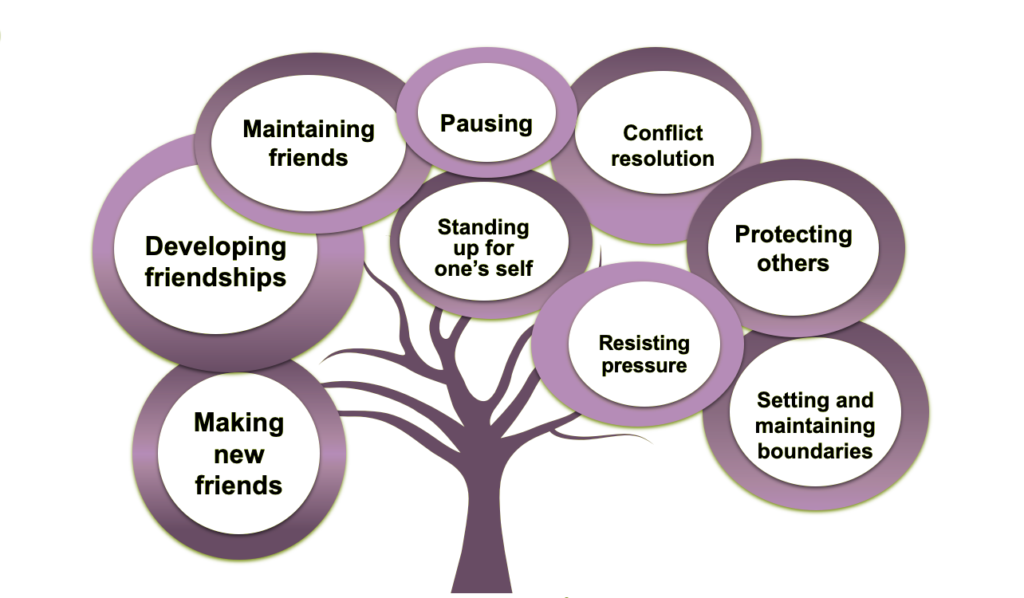

It is interesting that when a child is having friendship problems, parents will usually say, “Josie/Joe is having friendship problems at school.” In reality, what is often happening is Joe or Josie just hasn’t developed all of their friendship skills yet, neither have the children around them. The problem would be made manifest in any environment where peers were consistently present. This is where we need to step up.

Kids need to learn friendship skills and we need to teach them. That includes all kids. Ms Morgan says, “Every parent needs to put in work to teach their kids these skills. If your child is popular, check if they are playing the teenage social ‘game’. Are they using people, things, or social media to gain social currency? These gains are short-lived. Is your child including others and are they empathic? They are their best selves and develop the best friendships when they help others up, not when they push them down.”

6. Control your expectations and fears

As much as we hate to admit it, we sometimes contribute to our children’s friendship issues. We have expectations about how popular they should be and the sorts of friends they should have. Sometimes we panic if those expectations aren’t reaching fruition. It is not unusual for parents to ring their child’s school after the first couple of weeks of term, concerned that their child hasn’t got a best friend yet. These calls are about parental fear.

We worry if our kids don’t have ‘enough friends’ as though there is some magic number. That worry and fear is coming from a good place, but it is contagious and unhelpful. Children know if you think they are failing. What they need is for you to empower them.

Ms Morgan says, “You empower your child with your connection and your constant support. You empower them with realistic expectations and by encouraging them to jump into the skill gaps. By joining new groups and trying new things they can have lots of small wins and build their skills along the way.”

Finally…

The best thing about friendship issues happening at school is that it is an environment where there are caring, guiding adults involved; parents and teachers. We just have to constantly remind ourselves we are dealing with children. It’s not always obvious, but other people’s kids are just like ours; growing, learning, imperfect beings. They’re all just figuring it out and it’s our job to guide with compassion.

This article was first published by Lourdes Hill College on their blog, Inspiring Girls.