There have long been problems with ATAR, but now the statistics are leading us to ask…Does ATAR matter?

Talk to most 17 or 18-year-old Australians at the moment and they will no doubt get around to the fact that ATAR is looming large in their lives. Truth be known, it’s probably been looming large for years.

ATAR is also a hot topic of conversation among educators. Covid showed us that universities and students will still find one another if exams aren’t possible. So, should schools be spending quite so much time and so many resources on this aspect of education? It is not as though we don’t have other pressing concerns.

All this attention on ATAR is starting to show the system’s terminal problems, and those problems are starting to look like death blows. ATAR is dying…and that’s fine with many of us in education.

Who uses the ATAR?

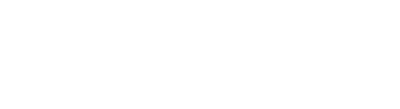

Approximately 50 % of Australian students go on to university studies at some point. Of them, 26% of students use an ATAR score to enter university. The rest use alternative entrance platforms. That means, approximately 13% of all students currently in Year 12 will actually use an ATAR.

13%

That means a large proportion of Australian school resources and focus is being spent on a very small proportion of students. That’s not equitable, fair, or right.

What is an ATAR?

The Australian Tertiary Admission Rank (ATAR) is a number between 0.00 and 99.95 that indicates a student’s position relative to all the students in their age group. It is not a mark, it is a ranking.

It is a complicated and convoluted system that puts a numerical value on disparate subjects like Physics and Dance and then compares them in order to rank students. It’s ridiculous. How can you possibly compare achievement in two such different subjects?

The average ATAR each year is close to 70. Yet, in WA, any ATAR below 60 was worthless. It would have been unlikely to have given access to university. Therefore, it is fair to say that doing an alternative course of study would have been the more astute choice for a large percentage of our kids.

Who does ATAR work for?

Universities

Until recently, it was believed that ATAR is great for universities. It literally provides them with a simple, transparent ranking of all students so they can scoop off the top proportion that they want.

However, even universities are using the ATAR less and less as an admittance tool. University of Canberra Vice-Chancellor Stephen Parker says, “To expect a single index to capture a person’s achievement to date and their potential for a particular course of study is simplistic and reductionist.”

The ATAR does not adequately capture the potential of a student to succeed at university. Consequently, many faculties are using portfolio work, interviews and school course work to accept students before ATAR results are even released.

In 2020, it became very clear that ATAR was not the be-all and end-all. Many universities guaranteed positions for students whether the exams went ahead or not. In 2021, more than 25,000 NSW students applied for an early offer through the ‘schools recommendation scheme’, in order to secure a place before sitting exams.

This trend has continued in 2022, with most universities reporting significant increases in numbers of offers made compared with previous years. Times are a changing!

Schools and parents

ATAR is an easy currency for schools and parents to trade in as it is the simplest way to measure school achievement. For high-achieving schools it is rolled-gold. However, surely, we want parents to choose schools for better reasons than ATAR results.

We want parents to look at values, community, student care, and the hundreds of great learning experiences offered both inside and outside of the daily timetable. At present, it is almost impossible to measure these much more important attributes.

Parents often like ATAR results as a measure because it is something that has been a constant from their own education. It is something they can relate to. But at what cost?

What is ATAR education costing us?

The ATAR is costing students, teachers, parents, and wider society:

1. Opportunities

- In focusing our time and resources on ATAR we are losing the opportunity to teach the skills that will transfer into the world beyond school. Skills like creativity, problem-solving, collaboration and citizenship. Yes, some of those skills are inherent to ATAR courses, however, it is still largely a knowledge-based assessment.

- The content that students are exposed to is distorted by a focus on the ATAR for up to five years of high school. There is also a much greater focus on testing as there is the belief that the more tests you do, the better you get at them. And that may well be true. Unfortunately, it results in students only valuing that which is tested. The refrain of “Is this in the test?” can kill a teacher’s love of teaching and closes a student’s mind to the amazing opportunities for learning that they could be accessing.

- A test-driven education puts the focus squarely on achievement and takes it away from teaching and learning. It is nearly impossible for the two cultures to co-exist. Yet most schools would claim that they strongly value great teaching and learning and that creating ‘a love of learning’ is central to their mission.

- We end up teaching students for an academic career, but that does not reflect the needs of our community. Why would we not educate for the society and students that we have?

2. Student wellbeing

There is no doubt that ATAR is contributing to stress in students. We might say, “Well that was the case in our day too”. However, when I was at school, in the 80s, the students who were university-bound sat university entrance tests. Now, due to government policy to keep kids at school and the more profit-driven approach of universities, there is a much greater range of students who are sitting ATAR.

Resilient Youth Australia survey over 600,000 students in their studies of Australian students. They report that 59% of Year 12 girls are suffering from clinical levels of anxiety. The number is only slightly lower for boys. Yes, there are other factors contributing to stress, it isn’t all ATAR, but it is front of mind for students. How is this ethical?

3. Student engagement

We know that in Australia, 20% of students are compliant but disengaged in our classrooms at any one time. That isn’t particular to one age range. It is across all age groups and genders. Our huge ATAR-driven curriculum of knowledge means that teachers have to deliver a lot of content in a short period of time. There is very little time for exploration and the development of engagement with learning.

4. Teacher burnout

With all of the rush and the focus on marks, teachers are left wondering, are we actually teaching a love of learning? It is dispiriting for a group of professionals who usually entered the profession due to their own love of learning. The pressure for good results is increased by league tables in the newspaper and the marketing programs in schools.

School administrations feel pressure and that is transferred to teachers. It is understandable that it happens, but ‘understandable’ is costing us a lot of teachers. Dr Donna Cross who is a researcher at UWA says “More than one-in-four Australian teachers suffer from emotional exhaustion after starting their careers and expect to leave the profession within the first five years of teaching.”

5. Is it equitable?

At the moment there is a heavy marks bias towards students from high socio-economic backgrounds. Whether this is correlation or causation is up for debate? However, there is a considerable gap between the haves and the have-nots and that gap is growing. Last year in Western Australia there were only four state schools in the top 20 performing schools in the ATAR.

6. Does it prepare kids for life in the workforce?

In today’s world, workers don’t need to know everything about their profession before they begin. All human knowledge is at our fingertips. Workers need the skills to find out and apply knowledge. We need to teach kids to be good at the things machines can’t do…human skills.

Education focussed on a test does not reflect the workplace or real life, where if you make a mistake, you have a chance to correct or improve your performance. The occasions where you have one chance to get it right under timed conditions with access to no resources are few and far between.

Will ending ATAR impact standards?

When a change to ATAR is discussed, there is usually the argument that removing ATAR would remove rigour in education. I don’t believe that’s true. It’s not about removing achievement from the picture, but to widen our focus to include skills and capabilities to enhance student outcomes for the future.

Competition will always exist for particular career paths, employers and universities will always find the best candidates. They may just need to do that work themselves, rather than putting the responsibility on schools to create a ranked list. Many of them would be more than happy with that.

What can we do now?

We can’t change the ATAR approach to education overnight, however, we can start making positive steps. We can:

1. Ensure students, parents and teachers are better informed about alternative entry to university.

2. Allow and empower teachers to really challenge students and let them explore, and sometimes fail, rather than focusing on passing exams.

3. Encourage kids to recognise internships and apprenticeships as valuable and sought-after career stepping-stones.

4. Be realistic about aptitude for tertiary studies at 18 years of age. Is an 18-year-old ready to decide on a course of education that can be worth many, many thousands of dollars? That debt will be with them for a very long time.

5. Ask whether ATAR is a good indicator of aptitude for university at all. Just because a young person can go to university, should they?

Finally…

All of this ultimately leads to the biggest question in education, how do we create a greater focus on learning than achievement? And is that even possible in our achievement-driven society?